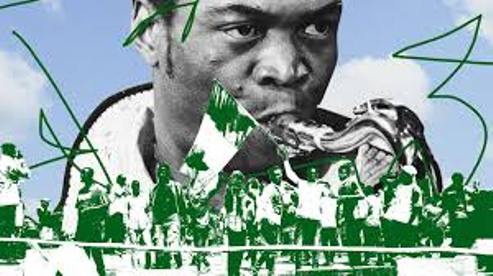

On Fela Kuti, #EndSARS And Cycles Of Oppression

LAGOS OCTOBER 31ST (NEWSRANGERS)-Fela Kuti’s 1989 song Beasts of No Nation was the first that the Afrobeat pioneer and Nigerian activist recorded after his twenty-month imprisonment under military rule of Muhammadu Buhari, Nigeria’s head of state from 1983-85.

Kuti was an active, audacious opponent of Buhari, who in turn sought to quiet him with bogus charges of currency smuggling—in the 28-minute epic, Kuti calls Buhari an “animal in craze man skin.” Buhari returned to democratically-elected power in 2015, and remains the current President of Nigeria.

The rhythm in Beasts of No Nation is held down by talking drums and call and response, voices working their part to create a beat that tugs at bone and muscle, making movement a demand, not an option. You move as lyrics are repeated to build towards a deeper narrative, gradually illuminating insight. Repetition here, is part of the progression, a reinforcement, strengthening the base for the next part of the song.

On the 20th of October 2020, 31 years after Beasts of No Nation was released, Nigerian soldiers shot into a crowd of peaceful protestors at Lekki Toll Gate, the most prominent in Lagos. The running, the confusion, the sorrow, the tears, and the blood were documented through shaky Instagram lives and frantic, breathless tweets. Bone-stiffening images flickered through timelines that moved too quickly, but somehow, also suspended Nigerians on the ground and throughout the diaspora in a distorted, nightmarish stillness. In his first address two days later, Buhari did not directly address the shootings, and told the international community to “seek to know all the facts before taking a position.”

The protestors were calling for the disbandment of the elite Nigerian police unit, SARS (Special Anti-Robbery Squad), which has mutated over the years into an extrajudicial gang that freely extorted, tortured, violated and murdered young Nigerians for anything from having the latest iPhone to wearing dreadlocks. Prior to the Lekki Toll Gate culmination, the atmosphere around the protests had been “really beautiful,” according to the British-Nigerian organiser Ayizan, who was at the gate hours before the shootings: “There was a sufficiency. People provided wifi, charging outlets, food, drinks, portaloos- people were even offering therapy. How do you organise free therapy? There were charging stations and cleaning crews every night. It was like the protests stretched our imagination to what Nigeria could be.”

The immediate spark for the demonstrations—dubbed “#EndSARS”—was the shooting of a young man by SARS in Delta State, Southern Nigeria, on October 8 that went viral. However, the larger context goes back decades, and is rooted in the gap between Nigeria’s ruling “gerontocracy,” as Wale Lawal, founder of the journal of African affairs, The Republic, describes it, and a new, technologically-savvy generation: “You see a gradual decline in a lot of public spending in Nigeria,” Lawal told me. “There is a systemic squeeze on resources. And then you have a technology boom that has led to young people being able to work in multiple formats, but as a society we haven’t necessarily caught up to that. So a SARS Officer has an impression these young people with laptops are doing 419, or Yahoo-Yahoo, [Nigerian slang phrases for fraud], but it isn’t the case. So you have a lot of people who are being arrested and represented as criminals, but aren’t given the due process. People end up getting brutalised in daylight, they get dragged on the streets to get kidnapped. And it worsens when you look at it across gender, sexuality and income levels. SARS officials will arrest rich people with connections, but these people are able to kind of negotiate or navigate their own way out of that. Whereas if you’re poor you don’t have those connections.”

Lawal says that the institutional resistance isn’t surprising. “What you find is a lot of the relationship between older people and younger people here tends to be built on systems that thrive on violence. When a system thrives on violence, the moment you try to eradicate that violence, it pushes back.” Yet, “young people rose above that,” he says. “They showed that young Nigerians are not going to just give their destinies on a platter.”

As the peaceful protests intensified and spread throughout the African diaspora, a mantra began to form online and on the ground, encapsulating anger at the Nigerian government. But it was also a chant of unity, an elevation of the voices of the Nigerian youth, demanding for the right to live without being terrorized.

Soro Soke. Translated from Yoruba, one of many indigenous Nigerian tongues, the phrase means, “Speak Up.” It is an encouragement, a reminder, a warning: we will not be silenced. We shall be heard. It was a demand addressed to the Nigerian government: you have been silent about our suffering, what will you do about it? Soro soke. What do you have to say for yourselves? Listen to what we have to say for ourselves.

Ayizan affirms that there’s an “innate audaciousness” to Nigerian millennials that “technology perhaps enables… Perhaps it is a product of social media, perhaps a product of our environment. We are the generation who want to live the life they want to. We are too audacious to just sit back and let this happen. Previously a state governor could downplay what happened. We watched this live.”

That generation is now dismayed by the unprecedented—at least within their lifetime—shooting at Lekki Toll Gate. A representative for the organization Feminist Coalition, which volunteered time to organize legal support and emergency medical services around the protests, told me that “people are really, really heartbroken.” The representative, who has been granted anonymity for security reasons, explained that “Maybe this was a bit naive of us, but I don’t think we expected that innocent protesters who were literally sitting down on the floor singing the national anthem would lose their lives and sustain so many injuries in the attack. I think the priority now for us is just encouraging people to be safe.”

In Fela Kuti’s 1977 song, Sorrow Tears & Blood, he croons over a bombastic marriage of jazz, funk and Yoruba syncopation. After a lengthy, rambunctious instrumental opening, we hear a response chorus of “Éè ya!” the Nigerian expression of dismay:

Éè ya

Police dey come, army dey come

Éè ya!

Confusion everywhere.

… Dem leave sorrow, tears and blood/ dem regular trademark (x7)

Sorrow Tears & Blood was released under the military rule of Olusegun Obasanjo, who later became President of Nigeria from 1999-2007. In the song Fela makes assertions on behalf of the Nigerian people, elevating their voice through his own:

We no wan die

We no wan wound…

I wan build house

I don build house

41 years later, Nigerian star Burna Boy’s 2018 afrobeat anthem Ye—a song which every young Nigerian everywhere will stop and hum and murmur and belt whenever it crosses their aural space—interpolated Fela’s hook:

But my people dem go say

I no wan kpai, I no wan die

I no wan kpeme, I wan enjoy

I wan chop life, I wan buy motor

I wan build house, I still wan turn up

Burna’s millennial voice builds upon the foundation Fela left, evolving his musical forefather’s demands for basic rights, and speaks to the aspirations of his generation. It’s a rallying chorus, a proclamation to survive as well as thrive, a desire for life to be savoured. It states: young Nigerians deserve the necessities and so much more. Repetition here is part of the evolution, moving us forward to the next song within a legacy.

Through the wreckage of hurt and disillusionment lie the embers of hope. The activists, organisers and thinkers I spoke to are hopeful that the moment will sustain itself and translate into political power. Lawal states that the protests were “one of the most significant exercises of hope that Nigerians have had for a very long time. It was like, if we can do this, we can potentially start to make the demands that we want to see in our society. If we can eradicate this thing that’s killing us, we can maybe start to think about ways to be more united, and to imagine a more progressive and better future for ourselves… whether we like it or not, the system has been ruptured. The protests were organised and decentralised, and unintentionally became an innovative mode of protest. I’m very careful not to call it a movement, because it was just one protest, but it could feed into a larger movement in a larger political way. For me it’s very likely to set us off on a positive trajectory that we’ve never seen before. ”

In the legal and medical services provided by Feminist Coalition, young Nigerians saw the future Nigerians they were fighting for represented, within touch, a totem of communal love and faith: “We kind of formed our own governance ecosystem around this entire movement,” the Coalition representative says. “ I think in our lifetime it was the first time we’ve ever really rallied and stood up and were unified on one topic… I don’t think this meant nothing. I think we made really good progress. Going forward, I feel like a lot of people are going to be way more interested in political elections. I think people are starting to realise that the power is actually in our hands. I think the 2023

[national]

elections will be widely different.”

That notion is echoed by Ayizan, who hopes that young people “can get to that stage where we have a solid political party. We need to form an entity. To those in the diaspora, keep making noise, if you can donate to causes on the ground do so, because there are very immediate problems going on right now. If you have the means to, contribute to the future of Nigeria.” Lawal too, looks to a progressive future, believing that the #EndSARS protests “could feed into a larger movement in a larger political way. If you go online, a lot of young Nigerian people are starting to discuss, what do we do next? How can we channel all this energy and all this infrastructure that we built, all the knowledge that we have about each other and what we’re capable of, into something more sustainable?” He warns that this is “very long, painstaking work that could take decades,” but says “I choose to lean on hope.”

In the early nineties, my father demonstrated against Nigerian military rule outside the Nigerian High Commission in London, with toddler me on his shoulder. Many other young Nigerians have similar experiences across the globe; hope for the future intimately wedded within our histories, diasporic tales woven into a larger tapestry. In 2020, as a British-Nigerian along with countless other Nigerians globally, I stand with our brothers and sisters who are in the home of our roots. Soro soke. Speak up. Past and present joining for the future, embedded with hope, drawing and generating power from each other, call and response, gathering strength along the way, and building, ever building. Perhaps the voice will grow to be loud enough to shatter a cycle. Soro soke.

GQ

Short URL: http://newsrangers.com/?p=59031